People & Pollinators: Event Guides

During Fall Quarter 2021, the EatWell Pod joined California Master Beekeeper Program manager

During Fall Quarter 2021, the EatWell Pod joined California Master Beekeeper Program manager

The EatWell Pod at Semel Healthy Campus Initiative annually celebrates Food Day…

Almost every home I visit hosts an eclectic mix of cookbooks, from one-pot keto guides to faded, hand-written family heirlooms. The cookbook shelf seems to me a quiet way of peeking into someone’s life, understanding how they spend time in the kitchen or with whom they share their secret recipes like prized relics. A household staple, cookbooks that float to and from strangers, loved ones, and children hold a seemingly universal and connecting role in our modern lives. However, it hasn’t always been this way. Like many elements of life that may seem commonplace, the cookbook at one time was a privilege for the wealthiest and the richest, a demarcating line between noble, middle-class, and poor.

The Truncated History of Cookbooks and Class

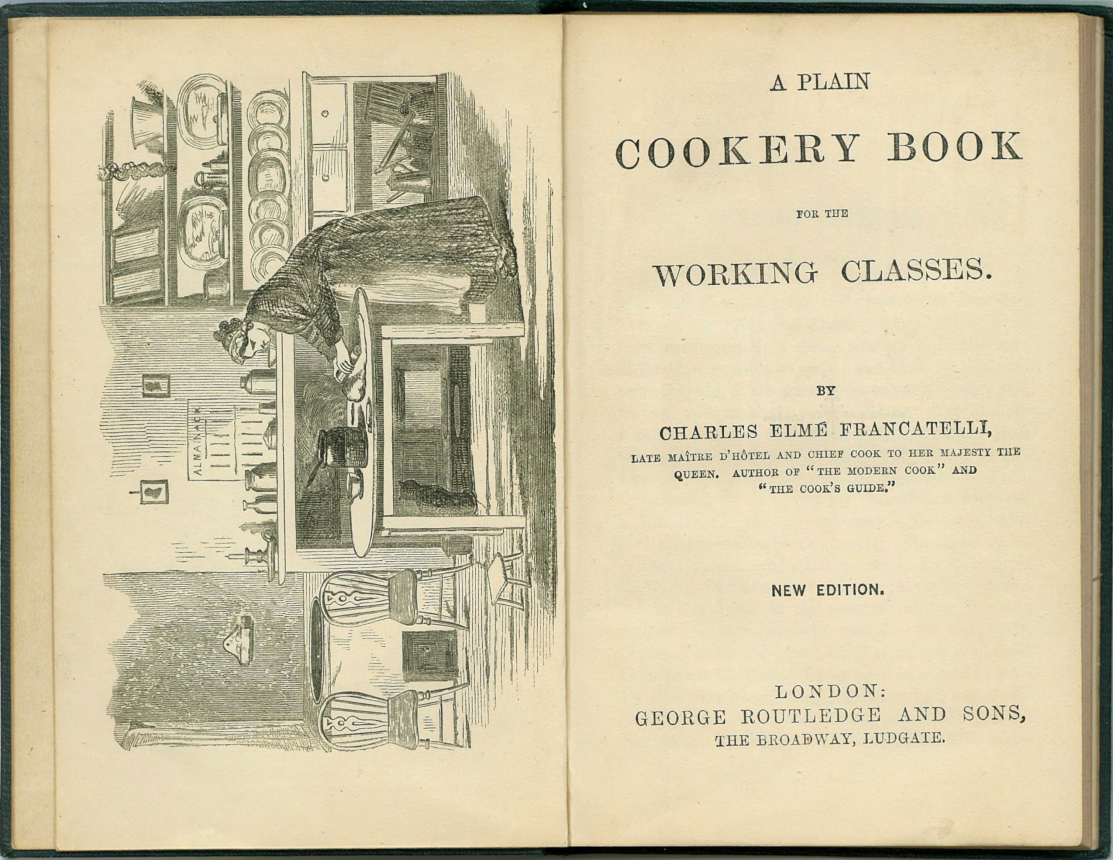

Before exploring some of the history of cookbooks, I want to mention that I’ll be speaking narrowly about the Western history of cookbooks, since those are what’re most readily available and published. The first recorded cookbook is said to be four clay tablets from 1700 BC in Ancient Mesopotamia, but by the 1300s, cookbooks were a norm for kings and nobles. In 1390, Forme of Cury (The Rules of Cookery) was published for–but not by–King Richard II. It contained recipes by the master-cooks, which you can see published in the 1780 print version here. In this cookbook, elements of southern European cooking surface–saffron, sugar, almonds, and various pasta recipes. Imagining what it would be like to taste and concoct these recipes is exciting, like indulging in the rich taste of the past. But it’s important to note that these ingredients, prepared and created by lower-class, were enjoyed solely by the rich bourgeoisie, carrying with them a fraught history of classism and exclusivity.

Photo source: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbc0001/2010/2010pennell31282/0008r.jpg

As mass printing and publishing increased by the 15th century and public literacy increased by the 17th century, cookbooks became less of a luxury, and somewhat of a standard. However, just because there was increased availability did not mean there was increased access. The type of recipes varied significantly according to class. The titles of cookbooks exemplified the role they played in perpetuating social hierarchy between the rich and poor, like in titles such as “Plain Cookery for the Working Classes,” “The Poor Man’s Larder and Kitchen” or “Fifteen-Cent Dinners for Working-Men’s Families” to name a few. On the other hand, recipes and books like “Les Soupers de la Cour” and “La Cuisiniere Bourgeoise” for royals and aristocrats.

Photo source: http://collection.hht.net.au/images_linked/48266.jpg

As the World Wars commenced in the early-mid 1900s, food gained a new meaning: they were about thriftiness, preservation, rationing, and efficiency. But after World War 2 as men came home and women were then expected to be traditional housewives, a domestic and feminized ideal in the kitchen and cookbooks emerged, coinciding with the rise of industrialized, canned, and processed food. This linked article outlines that in the 1950 Betty Crocker’s Picture Cookbook, the book says that “Just as every carpenter must have certain tools for building a house, every woman should have the right tools for the fine art of cooking.” Throughout these post-war cookbooks, it was clear that much of a woman’s worth was determined by her husband’s judgements of her adequacy as a mother, wife, or cook to her husband.

Photo source: https://sites.psu.edu/rclblogmgh/2018/09/06/bad-ad/

Now today, with the rise of Food Network and other food media like the Bon Appetit Test Kitchen, making meals seems trendy in a way, with a niche for everyone–vegans, meat-eaters, health nuts, and dessert geeks. As recipes and cookbooks have become digitized and integrated into our entertainment schema, they are possibly more normalized and maybe less explicitly allocated for rich or poor or male or female.

However, one could argue that class issues are not fully erased. As discussed in last month’s blog, just because food information exists doesn’t mean it’s readily available or distributed evenly. Recipes often contain expensive and exclusively ingredients, which make them inaccessible for low-income or food apartheid communities. Having a familiarity around and access to diverse recipes and various cookbooks is a privilege, and not one which all folks possess as many communities have been ostracized from farmers markets and bookstores for the sake of fast-food and convenience stores.

Racism and Exclusivity Today

In exploring the history of cookbooks throughout time, I would be remiss in not acknowledging that many recipes that circulated amongst white and wealthy families came from Black slaves; these books which we now see as a simple exchange of recipes are in many ways products of subjugating a race of people. This isn’t an extinct phenomena; it exists today when we witness the persistent reliance on Black Americans in growing, harvesting, and cooking food in the US or the racist “mammy” imagery reinforcing racial and gender roles in products “Aunt Jemima.” As explored in the link above, Black farmworkers who produce our very food are still experiencing abuse and maltreatment at the hands and the skewed benefit of their often white employers. Furthermore, the example of Aunt Jemima’s maple syrup, a name which has only just recently been replaced, illustrates how giant food corporations, like Quaker and PepsiCo, have abused racist imagery as a marketing tactic for their sole profit.

Although carrying a fraught, classist, and often sexist history, modern cookbooks hold a potential to decentralize and democratize meal-sharing. By re-interpreting the purpose of compiling recipes and the way we exchange cookbooks, we reclaim and revolutionize food knowledge. There’s something comforting and exciting about the story behind recipes– the paragraph or two that hooks readers or listeners about why this recipe holds significance. It brings a meal to life, connecting us intimately with the food and their stories. And these stories behind our food matter: they transform food into something more than sustenance, but as a way of understanding each other, telling stories, and caring for each other.

That’s why UCLA Farmers Market x Semel Healthy Campus Initiative Eatwell are collaborating to create a free, accessible community cookbook. We are featuring recipes from various students and campus groups to tell the story of meals, to support local farmers, and at large, to illustrate the diversity of voices and experiences that UCLA offers. We would love you to feature your own! We want you to share your story, and we want a space to collect recipes for free and for everybody.

Kayleigh Ruller is a third-year Human Biology and Society student, minoring in Food Studies at UCLA. Outside of Semel Healthy Campus Initiative, she leads the UCLA Farmers Market team, makes podcasts, and writes about the intersection of food, health, and culture. She finds inspiration by trying all the different restaurants in LA, drinking coffee to stay motivated, and cooking with her roommates in her free time!

References:

Notaker, Henry. “A 600-Year History of Cookbooks as Status Symbols.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 27 Oct. 2017, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/10/cookbooks-status-600-years/544164/.

“Shedding Light on Black and African American Farmworkers.” Farmworker Justice, www.farmworkerjustice.org/blog-post/shedding-light-on-black-and-african-american-farmworkers/.

Staves, Dana. “A Brief History of Cookbooks Worldwide.” BOOK RIOT, 19 Nov. 2019, bookriot.com/history-of-cookbooks/.

Fabrizio, Lauren E.. “Exploring the Domestic Ideology of the Postwar Era through Cookbooks.” (2015).

You’ve probably heard of food deserts. A lot of folks have studied, written about, and presented this issue in our industrialized food system. Importantly, a lot of folks may know what it is like to exist in and experience a space where access to fresh, affordable, and healthful foods is distant in proximity. But knowing about food deserts is different from existing in one.

I was not raised in a food desert and have an immense amount of privilege in writing about this issue, instead of actively worrying about it. I want to acknowledge this as I discuss and outline topics that are of utmost importance to me, but not directly impacting me.

Today I want to shed light on two concepts in the food justice realm: food apartheid and food sovereignty. It is in not only understanding these terms, but in bringing them into everyday vocabulary, academic papers, popular media, and policy write-ups to better equip us with an idea of how to address an unjust food system.

One way to direct the conversation around food inequity in America is to change our language.

The term food apartheid — versus food desert — more fully reflects that the lack of food access in communities like East LA or South Bronx or various rural and urban communities dispersed around the States is not a naturally occurring phenomenon the way the word “desert” implies. The phrase ‘food apartheid’ does not originate from me, but has been promoted by Karen Washington, a revolutionary community activist who addresses issues of intersecting forms of oppression of racism, health, food access, and poverty in New York. In an interview with Guernica, Washington described how the phrase food desert is an “outsider term”: people living in communities with low access to high-quality food do not describe their community as a “food desert”.

This struck a chord with me– despite its widespread use in the media, and in my very own essays– the term “food desert” does not capture the underlying reality of why there isn’t equitable access to healthy food. Washington advocates that the term “apartheid” better captures the entirety of the food system and invokes how social inequalities, implicit bias, and the racial worldview perpetuate a broken food distribution system. Racial inequities and capitalism, reinforced by large, industrial food corporations, are the roots of food apartheid.

We can take the example of how fast food chains are disproportionately present in low-income communities of color. When looking at the history of why and where McDonald’s franchises popped up, it’s clear that people in power used the allure of get-rich small business opportunities, like McDonald’s franchises, as a temporary, band-aid solution to equality in disenfranchised communities. It wasn’t a viable solution. It perpetuated “black capitalism,” which made owning a McDonald’s seem American, patriotic, and a means to gain social and political power. In reality though, McDonald’s franchising perpetuated a system of class and racial segregation with decades of health consequences, as described to Marcia Chatelaine’s Franchise: The Golden Arches in America. The inability for many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) communities to self-determine their food and health outcomes or to successfully resist the current cultural dominance of capitalist, corporate food systems, is an erasure of the history of oppression and the pinnacle of intersecting injustices: this is food apartheid as we see it.

So if capitalism can’t address food apartheid, what can?

Washington has some ideas. We can work to reduce the stigma around food pantries, and evolve these spaces to becoming accessible supermarkets that educate community members on how to prepare food. We could require charity organizations to transition leadership positions from founders or sponsors to actual community members. Public policy can reallocate subsidies toward grass-roots food initiatives, allowing communities to reclaim their food distribution and access with collective food sovereignty.

Food sovereignty is a concept created and promoted by La Via Campesina in the 1990s as a global movement as “the right of peoples and governments to choose the way food is produced and consumed in order to respect livelihoods,” as stated by Indigenous and environmental scholar Kyle Whyte. To work against this exploitative and culturally-dominant food production model is to also exercise autonomy over food systems– to pursue and possess food sovereignty. For many BIPOC communities whose foodways continue to be threatened and diminished by the repercussions of settler colonialism, true autonomy over food systems would look like a collective agency over their ability to produce, engage with, and share food in culturally appropriate ways.

I’ve thought about how when we say food desert, there’s this implicit idea that follows: well, if we add plants and life and richness to the land, maybe it will cease to be a desert anymore. But this, according to activists and scholars like Karen Washington and Kyle Whyte, is not the case. This mindset is one that believes a pretty, convenient band-aid can fix the toxic wound of an unjust food system. It ignores that life and richness already exists in these communities, and fails to convey the truth of resources having been stolen and replaced by harmful franchises. It endorses a morally arrogant notion that people in power can heal a broken community, when in reality the power already lives in the community. Changing language and inviting phrases like food apartheid and food sovereignty have the potential to rework the way we engage with topics of food access and food inequity. The language acknowledges a history of disenfranchisement, and empowers a sense of collective restoration for the future.

If you want to learn more about Food Apartheid, check out the recording of Eatwell’s Food for All Event online, featuring Karen Washington herself, among other leaders in the food justice and health equity.

Kayleigh Ruller is a third-year Human Biology and Society student, minoring in Food Studies at UCLA. Outside of Semel Healthy Campus Initiative, she leads the UCLA Farmers Market team, makes podcasts, and writes about the intersection of food, health, and culture. She finds inspiration by trying all the different restaurants in LA, drinking coffee to stay motivated, and cooking with her roommates in her free time!

References:

Brones, Anna. “Karen Washington: It’s Not a Food Desert, It’s Food Apartheid.” Guernica, 10 May 2018. www.guernicamag.com/karen-washington-its-not-a-food-desert-its-food-apartheid/.

Whyte, Kyle. (2017). Food Sovereignty, Justice and Indigenous Peoples: An Essay on Settler

Colonialism and Collective Continuance. Oxford Handbook on Food Ethics, (1-21).

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2925285

Guillen, R., & C2C. (2017). Growing Justice in the Fields: Farmworker Autonomy and Food

Sovereignty. In Pena D., Calvo L., McFarland P., & Valle G. (Eds.), Mexican-Origin

Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1t89jww.20Foods, Foodways, and Social Movements: Decolonial Perspectives (pp. 235-250).

Szalai, Jennifer. “The Surprising History of McDonald’s and the Civil Rights Movement.” The

New York Times, The New York Times, 8 Jan. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/01/08/books/review-franchise-golden-arches-black-america-marcia-chatelain.html.

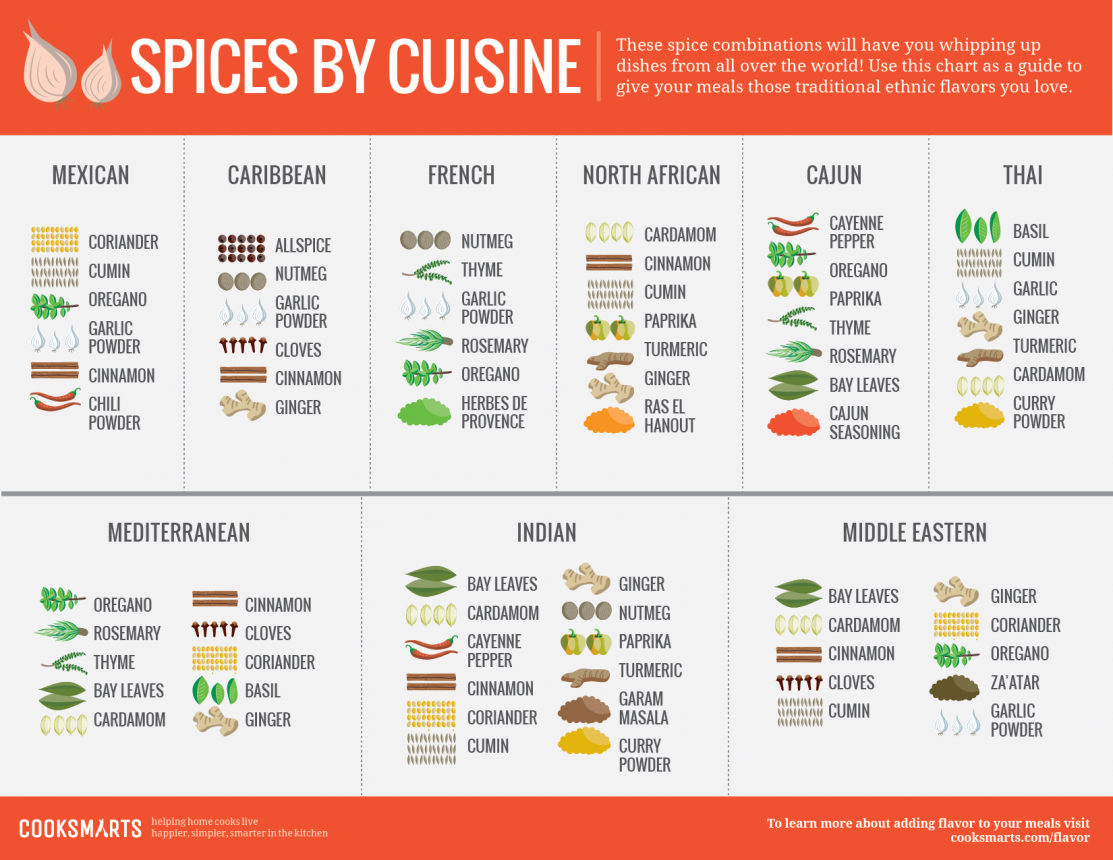

Maybe you’ve just started going back to restaurants as they’ve opened up, or perhaps you’ve been supporting local restaurants by ordering in throughout the stay-at-home orders. Otherwise, home-cooked food has been your mainstay for three months now. How many different spice palates have you experimented with?

Food is an integral part of culture, and the spices that flavor it are key. Think of cultural spice combinations as an art that has been perfected over hundreds or thousands of years in each part of the world. The spice trade created large trade routes that spread across the Eurasian continent, and initiated globalization. Some historians argue that “if the modern age has a definitive beginning, it was sparked by the spice trade.”

Try implementing one of these spice palates! If you’re unsure about the ratios, find a recipe that uses these spices.

Even with differing ingredients, using a similar spice palate can easily connect a dish back to its roots. For example, Hannah Che “veganizes” traditional Chinese recipes by using alternatives in place of meat when appropriate, but using the same spice palate.

In addition to the health benefit of making vegetables taste fantastic, spices have proven benefits of their own. Turmeric contains curcumin, a powerful antioxidant whose anti-inflammatory properties rival those of anti-inflammatory drugs. To get the full benefits of curcumin, pair turmeric with black pepper — black pepper contains piperine, which increases absorption of curcumin. Cinnamon can lower blood sugar and reduce risk of heart disease. If you’re consuming large doses of cinnamon, be sure to opt for Ceylon cinnamon rather than the more common Cassia cinnamon because Cassia cinnamon contains more of the harmful compound coumarin. Garlic can combat frequent colds, reduce blood pressure, and improve cholesterol levels, among other benefits.

Check out this article for more information on the health benefits of various spices.

This guide to seasoning your food discusses when to add certain spices and other flavors during cooking. For example, garlic, ginger, and chilis are usually added to the oil at the beginning, while garam masala is added last to ensure that it doesn’t burn. Sesame oil and lemon are also often added last because their flavors diminish quickly as they are cooked.

In general, powder spices are added midway through the cooking process to make sure that they don’t burn, but are also given time to develop in flavor. Fresh herbs, such as cilantro, are generally added towards the end so that their flavor and color stay intact.

The UCLA Teaching Kitchen is currently offering free virtual workshops every week, covering topics such as meal prepping, healthy baking, and kids’ cooking. If these workshops don’t fit into your schedule, you can find recorded videos of previous workshops on their website, along with additional videos and recipes!

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil and Environmental Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project, the Events Coordinator/Publicity Director for AWWA, and a member of the Club Sports Climbing Team.

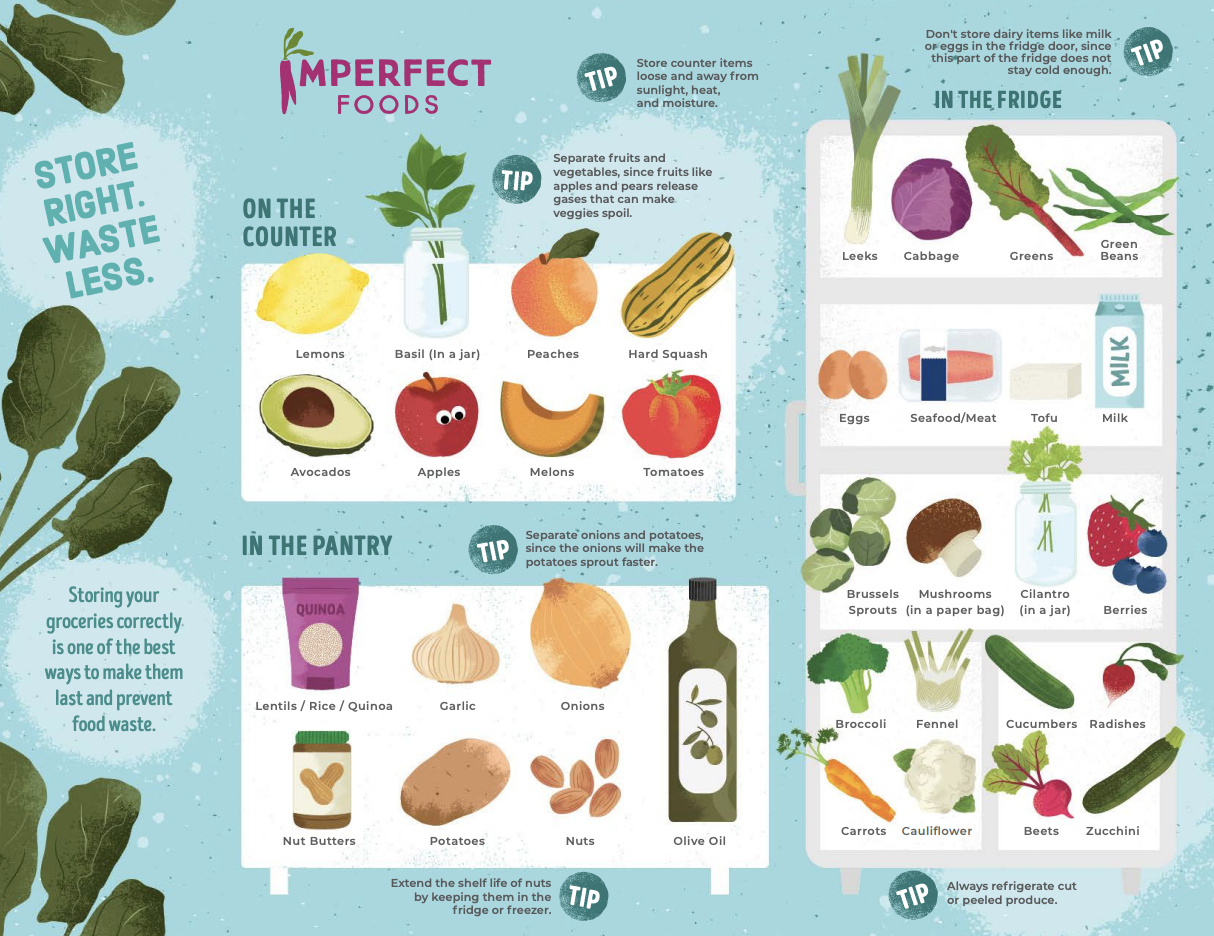

With grocery store trips now few and far between, it might feel extra appealing to extend the lifetime of foods, and perhaps even repurpose foods after they’ve completed their useful life. Giving a second life to your food scraps means producing less waste, discovering a new hobby, and depending on what you choose to do with your scraps, often saving money and needing fewer grocery trips!

Here are a few ideas to get started, ranked from easiest to most creative.

The easiest way to extend the lifetime of your groceries is to make sure that they’re stored where they stay fresh best. This isn’t always the refrigerator! Check out Imperfect Foods’ grocery storage guide blog post and their graphic below for more information.

Imperfect Foods (formerly known as Imperfect Produce) is a grocery delivery company which aims to reduce food waste across the US. Each week, they deliver a customized box of groceries which could not be sold at stores due to small imperfections, surplus, change of packaging, or short-coded best-by dates. Not only does this reduce food waste, it also reduces water usage and CO2 emissions, is often cheaper than grocery store pricing, and means fewer trips to the store per month! The company was featured in a previous EatWell blog post, found here.

In this article, Bon Appétit describes 14 innovative ways to use stale bread. These ideas include:

With a world of possibilities available for stale bread, consider giving one of these a try before tossing the whole loaf!

Don’t have a garden? Many vegetables can be regrown indoors, without any soil at all! This guide from Don’t Waste the Crumbs explains all you need to know about regrowing vegetables in water. Some of these veggies that will never need to be store-bought again include:

Broth is the perfect solution for food scraps that would be otherwise unusable. Homemade broth is inexpensive, requires little prep time, and is often much more flavorful than store-bought broth. To prepare to make food scrap vegetable broth, first collect clean food scraps in a container in the freezer.

Next, a quick Google search leads to hundreds of possible vegetable broth and bone broth recipes. For either of these types of broth, the base is the same: carrots, celery, and onion. To this base, you can add any bones left over from roasted meat, and almost all types of vegetable scraps you have on hand, with a few exceptions: cruciferous vegetables (e.g. cabbage and broccoli), green beans, zucchini, and starchy vegetables (e.g. potatoes).

Once you’ve made your broth, get creative and use it in recipes such as soups, stews, curries, and chilis!

A few weeks ago, @healthyucla (Semel HCI Center) went live with @zerowasteucla (an initiative by UCLA Sustainability) on Instagram to discuss and demonstrate vermicomposting. You can find a recap of their demo here.

Vermicomposting (“vermi” = worm) uses a worm bin to decompose food scraps, producing a robust, nutrient-rich fertilizer. This guide describes the 6 major steps of creating and maintaining a worm bin.

Use the resulting humus fertilizer in a vegetable garden, where you could even regrow other types of vegetable scraps!

If you have access to a garden, this might be a great option for you. This blog post from DIY & Crafts suggests 25 fruits and vegetables that can be regrown from kitchen scraps. These generally start out in water until their root system is well-established, then are transferred to soil.

A garden such as this one often grows faster than gardens grown from the seed up, since each plant has already established roots. Happy gardening!

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil and Environmental Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project, the Events Coordinator/Publicity Director for AWWA, and a member of the Club Sports Climbing Team.

In a perfect world, we would eat in harmony with our hunger signals, fully enjoy our meals, and choose more nutritious foods when possible. But this is often much more difficult than it sounds. Under societal pressure to look a certain way, 91% of college-aged women report having tried dieting at some point, and 61% of females and 28% of males report experiencing disordered eating. “Eating healthy” is not just about the food you eat, but is also about the relationship you have with food.

So what does a healthy relationship with food look like? According to the National Eating Disorders Association, “[a healthy] relationship includes relaxed eating, choosing preferences over positions, and practicing balance and flexibility in your eating.”

In this context, “relaxed eating” means eating in accordance with your hunger signals and understanding that these signals may change with your routine, moods, and physical demands. It also means that eating differently from one day to another should be no cause for alarm, judgement, or punishment.

“Preferences” refers to foods you prefer to eat, while “positions” refers to rigid habits and a fear of choosing other options. Thus, “choosing preferences over positions” means understanding that your preferences might not be suitable for every situation, and being content to choose from the other existing options.

“Balance” means “everything in moderation,” including all food groups. Unless you are avoiding certain foods for religious or ethical reasons, or have been instructed to do so by a doctor, there is no need to avoid eating any particular food. “Balance” also means eating for both pleasure and hunger, and avoiding diets (spoiler alert: diets don’t work anyway).

“Flexibility” is defined as “the absence of strict rules surrounding eating and food habits.” This includes removing the labels of “good/clean food” and “bad/junk food.” Some foods are more nutritious than others, but a healthy diet –and importantly, a healthy relationship with food– usually includes all types of foods.

In other words, a healthy relationship with food means the absence of obsession, restriction, anxiety, and guilt. In the second episode of the LiveWell podcast, Dr. Janet Tomiyama (PhD at UCLA in 2009) discusses her research on dieting and weight stigma, and the surprising factors that can drive us to eat, or not eat.

In this article, we will use Dr. Tomiyama’s definition of dieting: “cutting calories in order to lose weight.” This is often executed through commercial diet systems such as Weight Watchers, diets that remove specific macronutrients such as the keto diet and the Atkin’s diet, fad diets such as juice fasting, or simply counting calories and aiming below a certain daily threshold.

According to the Boston Medical Center, approximately 45 million Americans go on a diet each year, but there is little to no statistical evidence that diets result in long-term weight loss. Summed up in one sentence, Tomiyama describes her research as follows: “the main theme that goes through my research is that [a] punitive perspective on weight, size, stress eating and hanging out with friends is not productive.”

In fact, Tomiyama’s PhD research found that dieting releases stress hormones (cortisol), which may actually cause further weight gain. Even if short term weight loss occurs, the majority of studies she reviewed found that dieting is overall not a successful weight loss strategy.

This is logical, considering that deprivation of any sort can cause stress, even when the deprivation is self-inflicted. If you are considering a change in the way you eat, Tomiyama recommends focusing on adding more nutritious, healthful foods, rather than reducing “bad foods.” She also hopes that society’s view of health will shift to a focus on eating well, moving, less stress, sleeping well, and having good friendships without mentioning weight whatsoever.

In general, mentioning weight is not just rude, but may result in poorer health outcomes. Another paper by Dr. Tomiyama reveals that experiencing weight stigma is stressful, and as mentioned earlier, stress can cause further weight gain. Additionally, Tomiyama reports that people with a higher BMI may avoid the doctor more frequently due to fear of being shamed for their weight, which may result in health issues unrelated to their size. Again, it is best to avoid using weight as a metric for how healthy a person is.

Eating is not an exact science, and while counting calories in itself does not release cortisol, Tomiyama found that the practice increases perceived stress regardless. Tracking calories and macros (short for macronutrients: carbohydrates, fat, and protein) is popular among bodybuilders and athletes, but may not be necessary for the average person and may actually be detrimental for those that have a history of disordered eating. This article might help if you are deciding whether tracking macros would be beneficial to you.

The alternative to tracking your daily intake is intuitive eating. Intuitive eating means listening to your body, noticing how some foods might make you feel differently than other foods do, and eating when you are hungry, until you are full. It means rejecting diet culture, making eating enjoyable and non-stressful, and respecting yourself and your specific needs.

A search for a healthy eating practice that does not involve calories whatsoever brings us to the 80/20 approach. The 80/20 approach to eating suggests that approximately 80% of your foods should be minimally processed, plant-focused foods, and 20% is anything you would like to eat, perhaps the foods that you consider comfort foods. Although you’re eating 20% of less nutritious foods, there is no need to feel any remorse or guilt — comfort foods may actually increase your health in an unexpected way!

During an interview with Kaitlin Reid, MPH, RDN, for a previous blog post, I was curious about her experience with common misconceptions about food. Her response was surprising: “The main misconception that people have about food is that there are ‘good foods’ and ‘bad foods’.” She explained that labeling foods in such a way causes unnecessary stress when we eat ‘bad foods’, when in reality we should be able to enjoy these foods and move on.

What’s more, eating “comfort foods” without any guilt attached may be beneficial in reducing stress. Another major finding in Dr. Tomiyama’s research is that highly stressed individuals tend to engage in comfort eating, and that doing so results in lower cortisol levels. In the LiveWell podcast, she reveals that she is also currently looking into the possibility of transforming fruits and vegetables into “comfort foods” using Pavlovian conditioning.

While Tomiyama recognizes the ability of comfort eating to reduce stress, she also encourages using social rewards in place of food rewards when possible, and using a variety of other strategies to reduce stress. She also reminds podcast listeners, “people who don’t sleep well also find it really difficult to eat well. Sleep deprivation interferes with the parts of your brain that help you make healthy choices.”

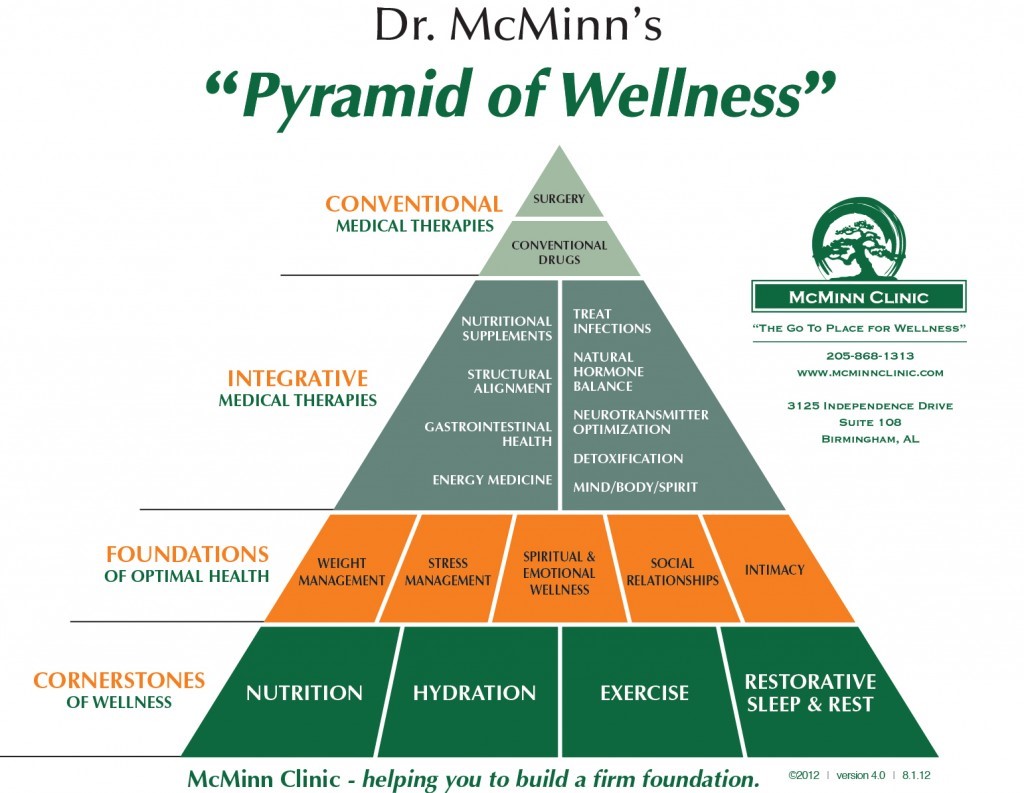

Reducing stress and sleeping more can improve not only your relationship with food, but also with yourself and with others. These relationships all contribute to overall health — a healthy relationship with food is just one piece in the multi-faceted puzzle of health and wellness. This relationship looks different for everyone, and it’s always important to be compassionate and open-minded, both with yourself and others. Here’s to listening to our bodies, being kind to ourselves, and making eating enjoyable!

If you think you or someone you love might be suffering from an eating disorder, please contact UCLA Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) at (310) 825-0768, or the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) Helpline at (800) 931-2237.

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil and Environmental Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project, the Events Coordinator/Publicity Director for AWWA, and a member of the Club Sports Climbing Team.

Eating healthy and exercising are good for your overall health and well-being, right?! Well, yeah! However, starting and maintaining a healthful lifestyle may, at times, seem daunting. Trying to eat a balanced diet, exercise 30 minutes 5 times a week, sleep a minimum of eight hours a day, and stay hydrated all while working, going to school, and spending time with family and friends; honestly, just writing that made me feel overwhelmed.

But do not fret. Though starting and maintaining healthful habits can be intimidating, there may be a solution within reach. What is it? Consider making small healthy changes that complement your lifestyle and preferences.

Studies show incorporating a small healthful change into your current lifestyle, as known as the “small changes approach,” can lead to improved health and healthy choices over time. Specifically, the “small change approach” suggests reducing your consumption of food or increasing your output of energy (exercising) by 100 calories. Although the approach recommends reducing a specific number of calories, promoters of “small changes” encourage food and beverage swaps that lead to a balanced diet, as opposed to counting calories.

Intrigued? Perfect! Now here is the fun part. How can you, a student, a parent, and/or a busy professional, make a change? Consider a slight alteration in your physical activity and/or food choices. Below is a list of suggestions outlining ways you can adopt ONE small change:

Replacing one sugary sweetened beverage (SSB), like soda or juice, for water, can decrease your calorie intake by as much as 200 kcal. If you miss the flavor of soda or juice, infuse your water with fruits and vegetables. Cucumber, Mint, and Lemon water is a refreshing take on SSB’s. Soaking pineapple and strawberries in water can give you the sweet kick you may crave. For more flavored water recipes, click here.

Similar to the study above, consider swapping an unhealthy snack for a healthful one. To create a healthy snack, combine foods high in nutrients like fiber, protein, and vitamins. Think apples and peanut butter, hummus and whole wheat pita, unbuttered air popped popcorn and trail mix, the possibilities are endless! Visit the American Heart Association for additional easy snacking ideas.

During the day, when are you walking? Maybe to your car, possibly around your job, or to class? Wherever you have opportunities to walk, consider extending the time and/or distance. If you are parking at a store, park further away from the front door. Take the stairs at your job. If you have time, take the long way to class. Karan Ishii wrote a fantastic article full of tips on how to make the most of your walking opportunities. Check it out!

Challenge yourself! Try ONE! If you would like to share, post on your social media with #uclalivewell.

Erica Lee MPH, RD, is the UCLA Upstream Obesity Solutions Grant Coordinator. In her capacity as a coordinator, she teaches UCLA health professional trainees the importance of healthful nutrition practices. In her free time, you can find Erica running, cooking a new recipe, and gardening.

If you’ve lived or worked on the Hill, you’ve likely had a chance to experience the exceptional quality and variety that UCLA’s dining halls have to offer. You may have also heard that UCLA has the best dining halls in the nation; this statistic comes from two notable rankings, Niche’s “2018 Best College Food in America”, where UCLA’s dining halls have topped the ranking for two out of the past three years, and Best Value Schools’ “50 Best Colleges with the Best Food”.

The “Best College Food in America” ranking focuses mainly on student surveys and usually represents the quality and flavor of the food offered. To include other key factors, such as sustainability and inclusiveness to all dietary needs, Best Value Schools compiled information from Niche, The Princeton Review, College Rank, the Daily Meal, and Best Colleges. According to these compiled statistics, UCLA came in 3rd place overall for 2017-2018!

Efforts over the past decade that have contributed to this ranking include the De Neve Flex Bar (2017), the inception of Bruin Plate (2013), and the thoroughly successful tray-free initiative (2009). These efforts, among others, support sustainability, nutrition, and students of all dietary needs and choices. But more ambitious goals lie ahead. UCLA Housing & Hospitality Services aim to reduce menu items with animal proteins by 10% by Spring 2020, while adding exciting plant-based dishes.

This fall, Rendezvous West added delicious (and shockingly realistic!) ImpossibleTM ground beef as a protein option in Build-Your-Own Burritos and Burrito Bowls, and in the California ImpossibleTM Burrito.

FEAST at Rieber is increasing their plant-centric options through dishes flavored with Indian spices such as “Spice Dusted Cauliflower, Yams, Charred Corn, Spinach, Spiced Pumpkin Seeds, and Avocado Mint Sauce”, and “Rajasthani Yellow Lentils, Nigella Seeds, and Micro Cilantro”. Adding these dishes and many others is a part of a continual effort to provide more authentic Asian foods at FEAST.

Bruin Bowl, a new dining location inspired by CAVA, Sweetgreen, and Tender Greens, is scheduled to open by Winter 2020. Located inside De Neve Commons, it will not only be easily accessible to students in the dorms, but also to students that walk to and from the apartments via De Neve Plaza. And yes, methods of payment other than BruinCard swipes will be accepted!

A delicious plant-based bowl from CAVA with falafel, hummus, and spicy lime tahini/green harissa (dairy free). Instagram: @cava

The link between sustainability and nutrition is complex, but one food sticks out like a sore thumb: beef.

In general, animal products have a much higher environmental impact than plant products. According to a study by Chatham House: The Royal Institute of International Affairs, greenhouse gas emissions from the livestock sector represent 14.5% of all greenhouse gas emissions and even exceed emissions from the transport sector. In this study, the ‘livestock sector’ is defined as the feed production, livestock production, slaughter, processing, and retail associated with all land-based-animals raised as food sources (including dairy and eggs).

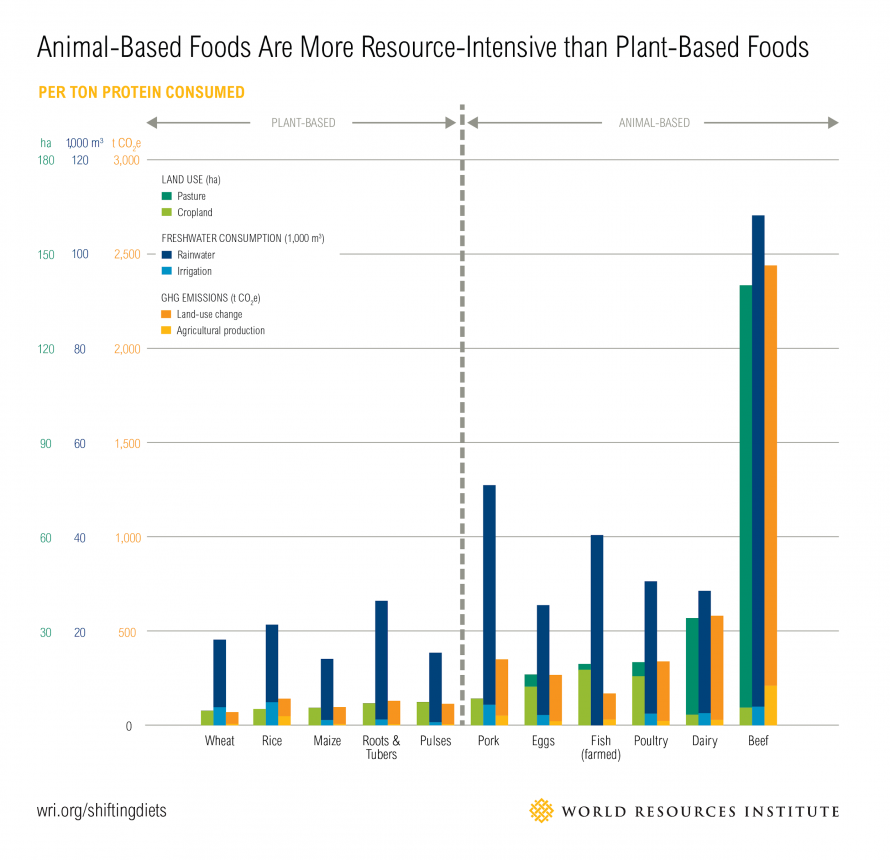

Similarly, a report published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization even sets the number as high as 18%. But beef is the most resource-intensive of all animal products by far. The three diagrams below help to visualize the environmental impact of beef compared to other proteins.

A comprehensive overview of the resources required to produce various proteins by the World Resources Institute.

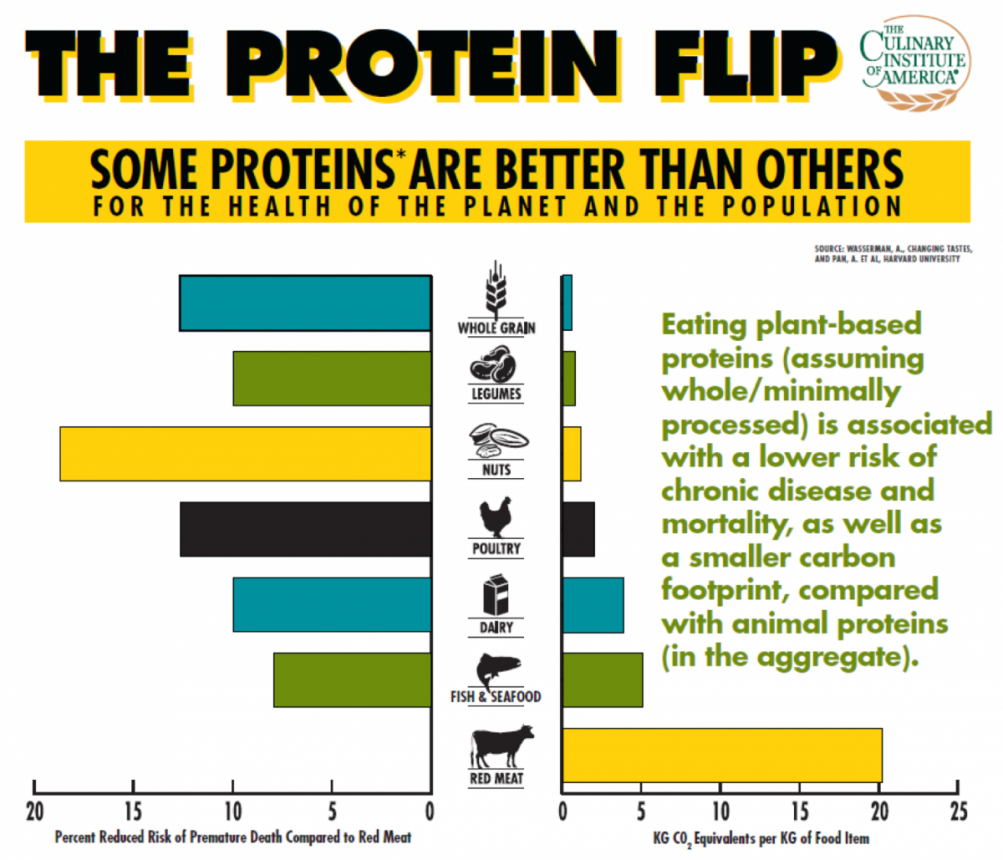

The link between sustainability and nutrition is shown in this graphic by The Culinary Institute of America.

In a previous blog post, Jennifer Jay, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, collaborated with the EatWell pod to create the infographic shown below. While beef and veggie burritos are comparable nutritionally, the carbon footprint of the beef burrito is 10x greater.

In the same article, Professor Jay writes,

“In addition to driving less and using less electricity, the FASTEST, EASIEST, AND BEST way to reduce our carbon footprint is to eat a plant-based diet. We do NOT need meat in our diet, and in fact, there is evidence to suggest that meat-heavy diets increase the risk of and exacerbate already-present chronic diseases, and are pro-inflammatory.”

You can find the whole infographic and more information from Professor Jay in the EatWell blog post here.

If asked, most people would say they are opposed to animal cruelty. But 94% of us contribute to the suffering of billions of animals, perhaps unknowingly, by eating animal products. This article clearly outlines the processes of transport, immobilization, and slaughter, and explains which parts of the process cause the animal to experience stress, fear, or pain.

And it’s not only the animals that suffer; slaughterhouse workers are increasingly being treated for PTSD and severe anxiety, and the psychologically taxing work is associated with increased domestic violence, social withdrawal, drug and alcohol abuse, and higher crime rates.

As one former slaughterhouse worker attests in the book Slaughterhouse: The Shocking Story of Greed, Neglect, and Inhumane Treatment Inside the U.S. Meat Industry:

“The worst thing, worse than the physical danger, is the emotional toll. If you work in the stick pit [where hogs are killed] for any period of time—that let’s [sic] you kill things but doesn’t let you care. You may look a hog in the eye that’s walking around in the blood pit with you and think, ‘God, that really isn’t a bad looking animal.’ You may want to pet it. Pigs down on the kill floor have come up to nuzzle me like a puppy. Two minutes later I had to kill them. … I can’t care.”

99% of farm animals in the US are raised on factory farms and numerous undercover investigations have revealed inhumane practices within the factory farming industry. More than 50 billion land animals are slaughtered yearly, and many more die on their way to the slaughterhouse due to heat stroke and diseases that run rampant in the impossibly close quarters that the animals occupy. In fact, 70-80% of all antibiotics are used for livestock for this very reason, which contributes to world antibiotic resistance.

Eating more plant-based foods and fewer animal products means changing lives: not only the lives of animals, but also the lives of the employees hired to kill them. Since supply follows demand, personal actions can genuinely make an impact when it comes to vouching for animal rights.

Some of the few very lucky cows that spend their lives outside, rather than in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFO). Image from flickr.com

To learn more about the nutritional benefits of eating more plant-based foods, I spoke with Erica Lee, MPH RD, who summed it up as follows:

“By eating more plant-based foods, you are more likely to consume the nutrients typically lacking in the American diet, especially fiber. Additionally, your risk for chronic diseases, such as heart disease, tends to decrease. But keep in mind, plant-based does not automatically mean healthy.”

For example, chips and soda are technically completely plant-based, but definitely not the best when it comes to health.

But what about eating a fully plant-based diet (ie. no animal products at all)? The position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics is that “appropriately planned vegetarian, including vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits for the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. These diets are appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, adolescence, older adulthood, and for athletes.”

Common worries about eating fully plant-based include not being able to get enough protein, iron, or calcium, difficulty reaching satiety, and high cost.

To ease these worries, Lee suggests identifying foods that contain high levels of protein (keep in mind that vegan bodybuilders get enough protein to build their impressive physiques without any animal products involved), iron, vitamin B12, and calcium, then choosing less processed foods such as beans and rice that happen to be much cheaper than animal products, focusing on flavor, and trying new recipes with these low-cost ingredients.

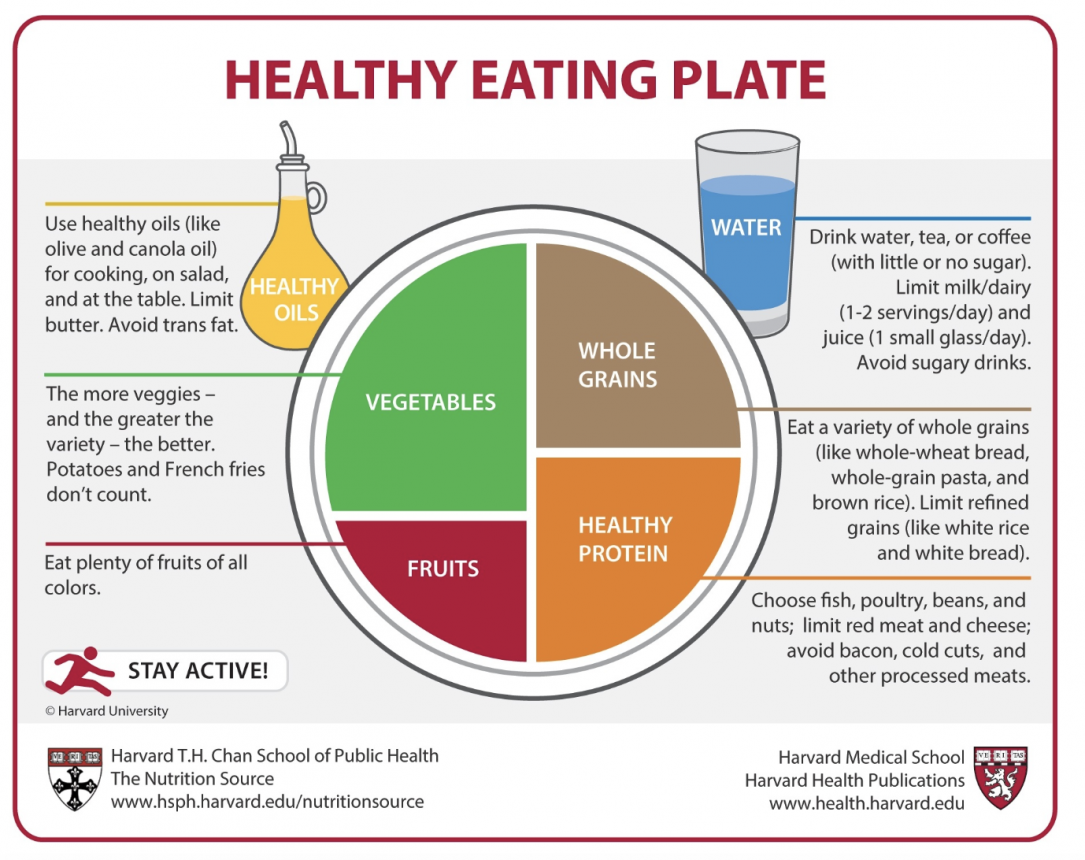

For those looking to transition to a fully plant-based diet, Lee recommends first checking out MyPlate or the Harvard Healthy Eating Plate (pictured below) and ensuring that your meals look similar. Next, focus on adding plant-based proteins and making replacements where possible, rather than only removing the foods that you no longer want to include. She also encourages looking for recipes of plant-based versions of the foods you already enjoy, eating as colorfully as possible, being kind to yourself throughout the process, and having fun with it! After all, your diet is constantly evolving and belongs to no one but yourself.

With some background on the benefits of choosing plant-based foods, it’s no surprise that UCLA strives to provide a variety of delicious plant-based options to keep our campus eating well. Dining on the Hill is constantly evolving, and your comments and suggestions are always welcome!

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil and Environmental Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project, the Events Coordinator/Publicity Director for AWWA, and a member of the Club Sports Climbing Team.

For the past few years, UCLA has hosted Teaching Kitchen classes at Sur La Table in Westwood. While these classes have been free for students, UCLA is required to pay to use their space, and there are extreme limitations on the number of students that can participate. In order to provide hands-on skills and food literacy to the wider student body, an on-campus teaching kitchen is scheduled to open on October 29th at the Los Angeles Tennis Center!

Food literacy is an incredibly nuanced term. See below for Kaitlin Reid’s (Nutrition Health Educator and Co-Founder, UCLA Teaching Kitchen) definition of food literacy. Try using it as a mental checklist for both the aspects of food literacy that you feel you understand well, and those that you’d like to learn more about.

“If someone were to improve their food literacy, they would essentially be improving their knowledge and skills, along with their attitudes and behaviors around food and nutrition. More specifically, someone with a higher degree of food literacy would:

Food literacy is about far more than basic nutrition.”

A Brief History of the “Teaching Kitchen”

While the importance of a healthy diet in achieving good overall health cannot be overstated, most medical education curricula lack sufficient training in nutrition. One study shows that only 25% of medical schools require students to take a nutrition course and fewer than 25% of physicians feel confident in discussing diet and exercise with their patients!

There is no surgery or prescription drug that can replace good nutrition. However, this message is not properly conveyed to medical students.

To remedy this, in 2006, the Culinary Institute of America and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health–Department of Nutrition launched the Healthy Kitchens, Healthy LivesⓇ conference, aiming to provide health professionals with both a greater understanding of nutrition science and the tools and recipes needed to make a lasting impact on their patients.

As the program grew, participating health professionals were motivated to create their own teaching kitchens, each of which operated separately from one another. The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative (TKC) was launched in 2016 in response to the need for a unified organization to oversee the many teaching kitchens. Now there are 41 teaching kitchens across the globe, eight of which are in California.

UCLA Teaching Kitchen at Sur La Table

UCLA has been part of the Teaching Kitchen Collaborative since 2016. Janet Leader (Associate Director of Nutrition Programs, Fielding School of Public Health) and Kaitlin Reid (Nutrition Health Educator, UCLA Student Health Education & Promotion) have been key pioneers in its inception and growth thus far.

When the UCLA Teaching Kitchen began hosting classes at Sur La Table in Westwood, the classes were geared solely towards health professional students. Since then, it has grown to reach the wider UCLA community, including classes for students recruited through Food Security Resources during Fall 2018.

The effects of these workshops on student wellness are promising: 96% reported an increased ability to eat balanced meals, 27% had connected with someone they met in class after one month, and 96% (an increase of 25% from the start) understood that half of your plate should be fruits and vegetables.

Graduate students participate in a Teaching Kitchen Class at Sur La Table in Westwood (2017).

Keep an Eye Out for the Launch of the On-Campus Teaching Kitchen on October 29th!

The future of the Teaching Kitchen is uncertain and exciting. The new kitchen at the tennis center has a maximum occupancy of only 12 students, but an auditorium/reception hall will be built to potentially serve larger groups. Some additional possibilities for ways to use the space are as a food prep area for those that don’t have access to a kitchen, training student interns in kitchen management, and hosting cultural food events.

Kaitlin Reid envisions an impactful future for the UCLA Teaching Kitchen:

“I believe [food] is the single most significant factor in the future of politics, environmentalism, economics, technology, health and healthcare, and ultimately of humanity. And if food is the future, now, more than ever before, education on food/nutrition is crucial.

What would it look like if every single student, staff, and faculty member were able (or perhaps even required!) to participate in experiential learning via the UCLA Teaching Kitchen? If UCLA is in fact, a birthplace of innovation and culture change, then why not dream really really big?”

For more information on the classes that have been hosted at Sur La Table, check out this blog post written by Kaitlin Reid in December 2017.

Finally, check out this resource for building the perfect meal in 5 simple steps! This beautiful infographic provides:

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project and the Events Coordinator/Social Media Manager for AWWA.