Faculty and Staff

Click here to add your own text

You’ve probably heard of food deserts. A lot of folks have studied, written about, and presented this issue in our industrialized food system. Importantly, a lot of folks may know what it is like to exist in and experience a space where access to fresh, affordable, and healthful foods is distant in proximity. But knowing about food deserts is different from existing in one.

I was not raised in a food desert and have an immense amount of privilege in writing about this issue, instead of actively worrying about it. I want to acknowledge this as I discuss and outline topics that are of utmost importance to me, but not directly impacting me.

Today I want to shed light on two concepts in the food justice realm: food apartheid and food sovereignty. It is in not only understanding these terms, but in bringing them into everyday vocabulary, academic papers, popular media, and policy write-ups to better equip us with an idea of how to address an unjust food system.

One way to direct the conversation around food inequity in America is to change our language.

The term food apartheid — versus food desert — more fully reflects that the lack of food access in communities like East LA or South Bronx or various rural and urban communities dispersed around the States is not a naturally occurring phenomenon the way the word “desert” implies. The phrase ‘food apartheid’ does not originate from me, but has been promoted by Karen Washington, a revolutionary community activist who addresses issues of intersecting forms of oppression of racism, health, food access, and poverty in New York. In an interview with Guernica, Washington described how the phrase food desert is an “outsider term”: people living in communities with low access to high-quality food do not describe their community as a “food desert”.

This struck a chord with me– despite its widespread use in the media, and in my very own essays– the term “food desert” does not capture the underlying reality of why there isn’t equitable access to healthy food. Washington advocates that the term “apartheid” better captures the entirety of the food system and invokes how social inequalities, implicit bias, and the racial worldview perpetuate a broken food distribution system. Racial inequities and capitalism, reinforced by large, industrial food corporations, are the roots of food apartheid.

We can take the example of how fast food chains are disproportionately present in low-income communities of color. When looking at the history of why and where McDonald’s franchises popped up, it’s clear that people in power used the allure of get-rich small business opportunities, like McDonald’s franchises, as a temporary, band-aid solution to equality in disenfranchised communities. It wasn’t a viable solution. It perpetuated “black capitalism,” which made owning a McDonald’s seem American, patriotic, and a means to gain social and political power. In reality though, McDonald’s franchising perpetuated a system of class and racial segregation with decades of health consequences, as described to Marcia Chatelaine’s Franchise: The Golden Arches in America. The inability for many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) communities to self-determine their food and health outcomes or to successfully resist the current cultural dominance of capitalist, corporate food systems, is an erasure of the history of oppression and the pinnacle of intersecting injustices: this is food apartheid as we see it.

So if capitalism can’t address food apartheid, what can?

Washington has some ideas. We can work to reduce the stigma around food pantries, and evolve these spaces to becoming accessible supermarkets that educate community members on how to prepare food. We could require charity organizations to transition leadership positions from founders or sponsors to actual community members. Public policy can reallocate subsidies toward grass-roots food initiatives, allowing communities to reclaim their food distribution and access with collective food sovereignty.

Food sovereignty is a concept created and promoted by La Via Campesina in the 1990s as a global movement as “the right of peoples and governments to choose the way food is produced and consumed in order to respect livelihoods,” as stated by Indigenous and environmental scholar Kyle Whyte. To work against this exploitative and culturally-dominant food production model is to also exercise autonomy over food systems– to pursue and possess food sovereignty. For many BIPOC communities whose foodways continue to be threatened and diminished by the repercussions of settler colonialism, true autonomy over food systems would look like a collective agency over their ability to produce, engage with, and share food in culturally appropriate ways.

I’ve thought about how when we say food desert, there’s this implicit idea that follows: well, if we add plants and life and richness to the land, maybe it will cease to be a desert anymore. But this, according to activists and scholars like Karen Washington and Kyle Whyte, is not the case. This mindset is one that believes a pretty, convenient band-aid can fix the toxic wound of an unjust food system. It ignores that life and richness already exists in these communities, and fails to convey the truth of resources having been stolen and replaced by harmful franchises. It endorses a morally arrogant notion that people in power can heal a broken community, when in reality the power already lives in the community. Changing language and inviting phrases like food apartheid and food sovereignty have the potential to rework the way we engage with topics of food access and food inequity. The language acknowledges a history of disenfranchisement, and empowers a sense of collective restoration for the future.

If you want to learn more about Food Apartheid, check out the recording of Eatwell’s Food for All Event online, featuring Karen Washington herself, among other leaders in the food justice and health equity.

Kayleigh Ruller is a third-year Human Biology and Society student, minoring in Food Studies at UCLA. Outside of Semel Healthy Campus Initiative, she leads the UCLA Farmers Market team, makes podcasts, and writes about the intersection of food, health, and culture. She finds inspiration by trying all the different restaurants in LA, drinking coffee to stay motivated, and cooking with her roommates in her free time!

References:

Brones, Anna. “Karen Washington: It’s Not a Food Desert, It’s Food Apartheid.” Guernica, 10 May 2018. www.guernicamag.com/karen-washington-its-not-a-food-desert-its-food-apartheid/.

Whyte, Kyle. (2017). Food Sovereignty, Justice and Indigenous Peoples: An Essay on Settler

Colonialism and Collective Continuance. Oxford Handbook on Food Ethics, (1-21).

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2925285

Guillen, R., & C2C. (2017). Growing Justice in the Fields: Farmworker Autonomy and Food

Sovereignty. In Pena D., Calvo L., McFarland P., & Valle G. (Eds.), Mexican-Origin

Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1t89jww.20Foods, Foodways, and Social Movements: Decolonial Perspectives (pp. 235-250).

Szalai, Jennifer. “The Surprising History of McDonald’s and the Civil Rights Movement.” The

New York Times, The New York Times, 8 Jan. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/01/08/books/review-franchise-golden-arches-black-america-marcia-chatelain.html.

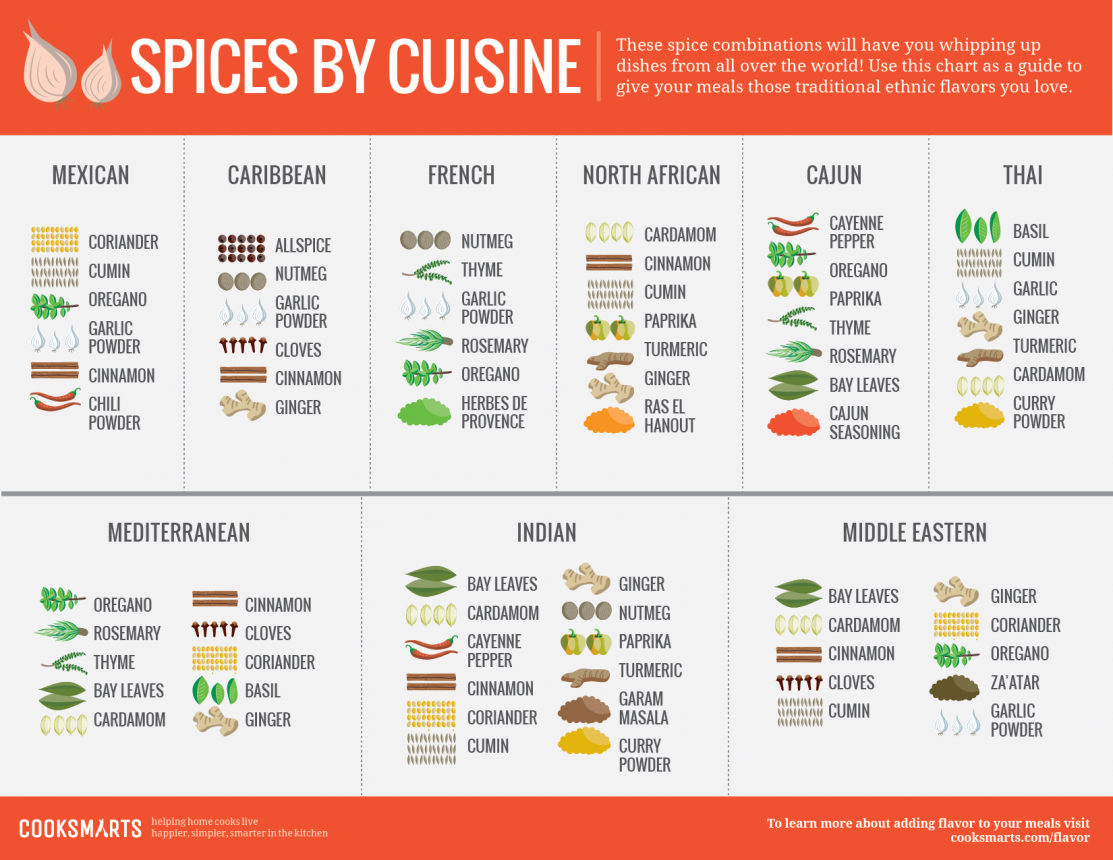

Maybe you’ve just started going back to restaurants as they’ve opened up, or perhaps you’ve been supporting local restaurants by ordering in throughout the stay-at-home orders. Otherwise, home-cooked food has been your mainstay for three months now. How many different spice palates have you experimented with?

Food is an integral part of culture, and the spices that flavor it are key. Think of cultural spice combinations as an art that has been perfected over hundreds or thousands of years in each part of the world. The spice trade created large trade routes that spread across the Eurasian continent, and initiated globalization. Some historians argue that “if the modern age has a definitive beginning, it was sparked by the spice trade.”

Try implementing one of these spice palates! If you’re unsure about the ratios, find a recipe that uses these spices.

Even with differing ingredients, using a similar spice palate can easily connect a dish back to its roots. For example, Hannah Che “veganizes” traditional Chinese recipes by using alternatives in place of meat when appropriate, but using the same spice palate.

In addition to the health benefit of making vegetables taste fantastic, spices have proven benefits of their own. Turmeric contains curcumin, a powerful antioxidant whose anti-inflammatory properties rival those of anti-inflammatory drugs. To get the full benefits of curcumin, pair turmeric with black pepper — black pepper contains piperine, which increases absorption of curcumin. Cinnamon can lower blood sugar and reduce risk of heart disease. If you’re consuming large doses of cinnamon, be sure to opt for Ceylon cinnamon rather than the more common Cassia cinnamon because Cassia cinnamon contains more of the harmful compound coumarin. Garlic can combat frequent colds, reduce blood pressure, and improve cholesterol levels, among other benefits.

Check out this article for more information on the health benefits of various spices.

This guide to seasoning your food discusses when to add certain spices and other flavors during cooking. For example, garlic, ginger, and chilis are usually added to the oil at the beginning, while garam masala is added last to ensure that it doesn’t burn. Sesame oil and lemon are also often added last because their flavors diminish quickly as they are cooked.

In general, powder spices are added midway through the cooking process to make sure that they don’t burn, but are also given time to develop in flavor. Fresh herbs, such as cilantro, are generally added towards the end so that their flavor and color stay intact.

The UCLA Teaching Kitchen is currently offering free virtual workshops every week, covering topics such as meal prepping, healthy baking, and kids’ cooking. If these workshops don’t fit into your schedule, you can find recorded videos of previous workshops on their website, along with additional videos and recipes!

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil and Environmental Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project, the Events Coordinator/Publicity Director for AWWA, and a member of the Club Sports Climbing Team.

With grocery store trips now few and far between, it might feel extra appealing to extend the lifetime of foods, and perhaps even repurpose foods after they’ve completed their useful life. Giving a second life to your food scraps means producing less waste, discovering a new hobby, and depending on what you choose to do with your scraps, often saving money and needing fewer grocery trips!

Here are a few ideas to get started, ranked from easiest to most creative.

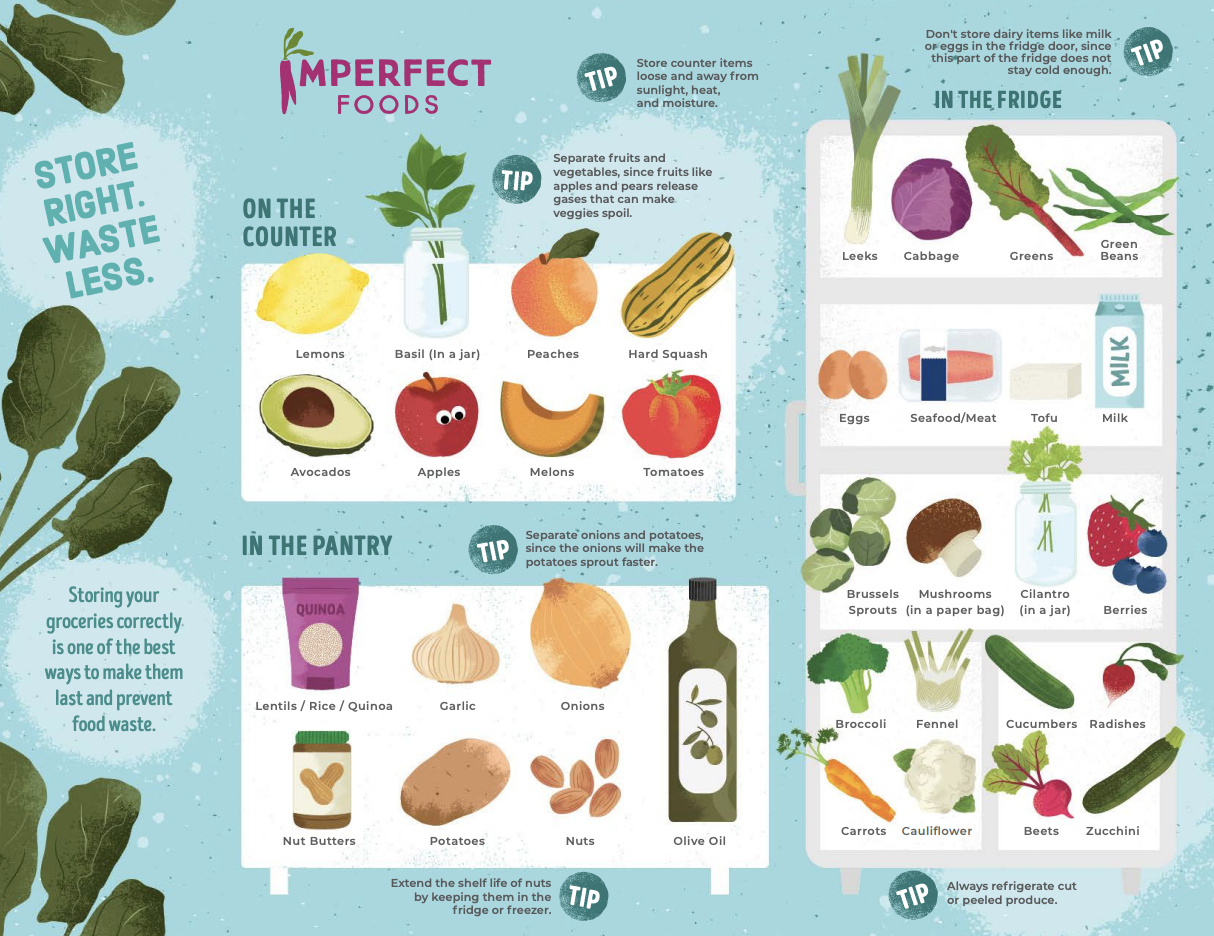

The easiest way to extend the lifetime of your groceries is to make sure that they’re stored where they stay fresh best. This isn’t always the refrigerator! Check out Imperfect Foods’ grocery storage guide blog post and their graphic below for more information.

Imperfect Foods (formerly known as Imperfect Produce) is a grocery delivery company which aims to reduce food waste across the US. Each week, they deliver a customized box of groceries which could not be sold at stores due to small imperfections, surplus, change of packaging, or short-coded best-by dates. Not only does this reduce food waste, it also reduces water usage and CO2 emissions, is often cheaper than grocery store pricing, and means fewer trips to the store per month! The company was featured in a previous EatWell blog post, found here.

In this article, Bon Appétit describes 14 innovative ways to use stale bread. These ideas include:

With a world of possibilities available for stale bread, consider giving one of these a try before tossing the whole loaf!

Don’t have a garden? Many vegetables can be regrown indoors, without any soil at all! This guide from Don’t Waste the Crumbs explains all you need to know about regrowing vegetables in water. Some of these veggies that will never need to be store-bought again include:

Broth is the perfect solution for food scraps that would be otherwise unusable. Homemade broth is inexpensive, requires little prep time, and is often much more flavorful than store-bought broth. To prepare to make food scrap vegetable broth, first collect clean food scraps in a container in the freezer.

Next, a quick Google search leads to hundreds of possible vegetable broth and bone broth recipes. For either of these types of broth, the base is the same: carrots, celery, and onion. To this base, you can add any bones left over from roasted meat, and almost all types of vegetable scraps you have on hand, with a few exceptions: cruciferous vegetables (e.g. cabbage and broccoli), green beans, zucchini, and starchy vegetables (e.g. potatoes).

Once you’ve made your broth, get creative and use it in recipes such as soups, stews, curries, and chilis!

A few weeks ago, @healthyucla (Semel HCI Center) went live with @zerowasteucla (an initiative by UCLA Sustainability) on Instagram to discuss and demonstrate vermicomposting. You can find a recap of their demo here.

Vermicomposting (“vermi” = worm) uses a worm bin to decompose food scraps, producing a robust, nutrient-rich fertilizer. This guide describes the 6 major steps of creating and maintaining a worm bin.

Use the resulting humus fertilizer in a vegetable garden, where you could even regrow other types of vegetable scraps!

If you have access to a garden, this might be a great option for you. This blog post from DIY & Crafts suggests 25 fruits and vegetables that can be regrown from kitchen scraps. These generally start out in water until their root system is well-established, then are transferred to soil.

A garden such as this one often grows faster than gardens grown from the seed up, since each plant has already established roots. Happy gardening!

Patience Olsen is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Civil and Environmental Engineering. In addition to blogging for the EatWell pod, she is a PD for the ASCE Environmental Design project, the Events Coordinator/Publicity Director for AWWA, and a member of the Club Sports Climbing Team.