Cooking with Apicius: A Mediterranean Kitchen in Westwood

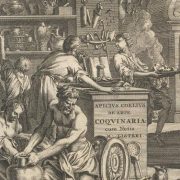

The trans-disciplinary course Food and Medicine in Antiquity, taught by Alain Touwaide during Spring Term, culminated with a Roman dinner organized in collaboration with The Huntington in San Marino. In keeping with the theme, a centuries old text took center stage: an ancient cookbook known as Apicius, De re coquinaria (On the culinary art). Though attributed to Marcus Gavius Apicius, a wealthy 1st century BC/AD Roman gourmet, the cookbook is a 4th/5th century compilation that includes some recipes possibly dating back to Apicius.

On Sunday June 3, students enrolled in the course who come from a vast array of disciplines (including but not limited to classics, history, anthropology, biology, microbiology, environment studies, economics, communication, design, arts, and theater), enjoyed a 5-course menu in the Mediterranean tradition. Student and apprentice chef Sophia Denison-Johnston created this menu: for appetizer a cheese- and garlic spread with olives; for the main course, chicken in red wine and garum, fish with a pesto-like mix of herbs and spices, and asparagus with a mousseline; for dessert, dried fruits.

This experience of applied history was a truly unique opportunity to bring the classics to life and to explore the roots of the Mediterranean diet. Not only did student enjoy its health-promoting benefits, they also engaged with a cultural approach to nutrition and the human dimension of collaboratively preparing and enjoying a meal.

The Semel HCI Center invited Sophia Denison-Johnston and Andrea Zachrich, students in the course, to share their experience of preparing Apicius’ dishes.

Hors-d’oeuvre of apricots

with Andrea Zachrich

Apicius’ text

Apicius IV.5.4

Take firm, early or undersized fruits, wash them, remove the stone and put them (to cook) in cold water and then arrange them in a dish. Pound pepper, dried mint, pour on liquamen, add honey, passum, wine, and vinegar; pour over the apricots in a dish, add a little oil and let it come to heat over a gentle fire. When it is simmering, thicken it with starch, sprinkle with pepper and serve.

This recipe does not give the cook much to work with, and some of its ingredients do not exist anymore, such as the garum. I attempted to find ingredients as close as.

Ingredients

5 Apricots

1 tablespoon pepper

1 tablespoon mint

1 tablespoon fish sauce

2 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons sweet raisin wine

2 tablespoons red wine

2 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

Extra Virgin Olive Oil

1 tablespoon cornstarch

Substitutions

- Apricots: Apricots existed in antiquity, but the Romans classified them as a kind of plum they called an “armenian plum” or “prunus armeniaca”.

- Pepper: Similar to apricots, pepper in a form close to the modern form existed in antiquity as well. It was traded from India, and was very expensive. During the time of Pliny the Elder (1st AD) it could cost as much as 12 denarii per pound, which was around 2 weeks pay for a soldier.

- Mint: Peppermint grows widely around the Mediterranean. While the species for this recipe is not specified, we gain a clue from Pliny when he states that peppermint is used for dishes at “entertainment” or dinner parties.

- Fish Sauce: The Romans had a unique fish sauce called garum or liquamen which was usually made from mackerels fermented in big barrels in the sun for months. This is not made anymore, but similar types of fish sauces exist in Southeast Asia. The one I used was called “Red Boat Fish Sauce”, a nous nam sauce from Vietnam made from fermented anchovies.

- Honey: Honey was widely used in antiquity, and almost every estate had its own beehives. The Romans thought it was a gift from the gods that was similar to the the nectar drunk by the gods on Mount Olympus.

- Sweet Raisin Wine: In antiquity, this kind of wine was called passum. It still exists today in the form of a wine called straw wine, but it is very expensive at around 20 dollars a bottle in its cheapest form. As such, I made some based off of a recipe from Columella, De Re Rustica, a 1s –century AD book about agriculture. This involved soaking raisins in wine for a few days until they were saturated, mashing them into the wine, and then straining the wine through a cloth. Photo 2 here

- Red Wine: Wine was widely drunk in antiquity, usually mixed with water. Unlike water, wine was guaranteed to be free of bacteria. Today’s wine, however, is different from ancient wine. The process to make the wine, however, would have been similar.

- Balsamic Vinegar: This also would have been similar to how it was made in antiquity because modern and ancient vinegar are both made with old wine. Vinegar was widely used in antiquity, both in cooking and in a drink called posca, which was water mixed with vinegar that was popular among soldiers and lower classes.

- Extra Virgin Olive Oil: This is probably the closest ingredient we have to the ancient one because it is still made in the same way today. According to the USDA guidelines, extra virgin olive oil must only be the juice from a pressed olive without any modifications from heat, etc. Ancient olive oil would have been made in the same way.

- Cornstarch: The ancient starch most similar to this was called amylum, although this kind of starch was made from wheat instead of corn. It was a fine starch used to thicken sauces, or could also be used by itself with milk as a kind of pudding.

Directions

- Take the apricots and wash them and remove the pits. Put the apricots in a bowl of cold water while you make the sauce.

- For the sauce: Mix the pepper, mint, fish sauce, honey and sweet raisin wine. Set aside.

- Cut the apricots in half and put them in a cast iron pan. Pour the sauce over the apricots. Put them on the stove on low heat and add a little olive oil.

- When the sauce starts to bubble, add the cornstarch and stir the sauce.

- Heat the apricots until soft. Take off the fire, sprinkle with pepper, and serve.

Boiled fish with a sauce of herbs and spices, and peas

with Sophia Denison-Johnston

Apicius’ text

Sauce for Boiled Fish

Apicius X.1.2

Pepper, lovage, cumin, onion, oregano, pine nuts, date, honey, vinegar, liquamen, mustard, a little oil. Serve the sauce hot. If you want, add raisins.

Peas

Apicius V.3.4

Cook the peas, stir them and put the pan in cold water; when it has gone cold, stir again. Chop onion finely with cooked white of egg, season with oil and salt, and add little vinegar. Pass cooked egg yolk through a sieve on to the peas in their serving dish. Poor green oil on top and serve.

Ingredients (with substitutions for modern times)

- Peas: Use frozen peas.

- Fish: Use a white fish.

- Oil: Extra Virgin Olive oil is best.

- Salt: Use kosher sea salt.

- Lovage: When researching this herb, I learned that it is no longer commonly grown. It has a sharp bitter flavor, and is almost always paired with pepper. My substitute was a combination of celery leaves and parsley, which has grown popular as a a modern, milder substitute for lovage. The celery leaves were used to add back in a sharper bitter note that lovage was known for (Faas 2003: 151)

- Vinegar: Use white wine vinegar if possible. If necessary, substitute for red wine vinegar.

- Liquamen: Liquamen, or garum, is no longer produced in the Mediterranean today. It is a fermented fish sauce created by combining whole fish with herbs, water, and sometimes wine, and allowing them to ferment for a whole summer in large stone vats. To substitute for this no-longer used ingredient, I used fish sauce from an asian foods market. exception of herbs or flavorings that could have been added in the mediterranean region.

Preparation: While Apicius lists the ingredients and sometimes will refer to method, usually the methods are assumed to be known. Here, I have outlined in greater detail the methods I used when cooking these two dishes.

Peas

- Boil egg: Place egg in saucepan with water. Bring water to boil. Once boiling, turn off heat, cover, and let sit for 10 minutes. Place in ice water to cool. Once cooled, peel.

- Boil peas: Place peas in 1/4 cup boiling water per 1 cup frozen peas. Bring back to a boil. Once boiling, turn down heat, cover, and let simmer for 6 minutes.

- Chop 1/4 onion and egg white, season with 1/2 tsp kosher salt, 2 tsp olive oil, 1 tsp red wine vinegar, mix.

- Press yolk through strainer into pea mixture. Add a touch more olive oil, and serve.

Fish with sauce

- Cook fish: Steam the fish and season with salt.

- The sauce: Traditionally, the sauces are prepared with a mortar and pestle, however I did not have access to one so I used a food processor. Begin by pulsing the herbs and pepper, followed by adding dates and honey. Finally, add vinegar, and olive oil, tasting as you go along to ensure the right amount is added. Finally, add the liquamen, only 5 drops at a time, so that enhances the flavor that is already there without overpowering it.

Taste

The peas were delicious! The peas themselves were sweet, with a more salty and savory flavor that balances out the sweetness of the peas. The dish was very light, yet filling, and satisfying along with the fish.

The fish itself was quite plain, but this is intentional in order to highlight the sauce. The sauce tastes much like a pesto; the strongest flavors coming through were the herbs and nuts, with the sweet dates and honey balancing out the sharper vinegar, bitter herbs, pepper, and fish sauce.

References:

Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger (eds and trs.), Apicius. A critical edition with an introduction and an English translation of the Latin recipe text Apicius. Totnes: Prospect Books, 2006, pp. 203, 213 and 301.

Patrick Faas, Around the Roman Table. New York, NY, and Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003, pp. 131, 151, 153

—